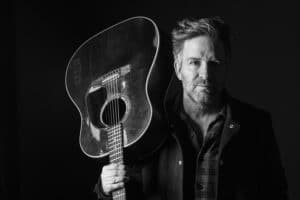

Blank Range’s Jonathon Childers: ‘There’s joy in a sober lifestyle’

Blank Range's Jonathon Childers: 'There's joy in a sober lifestyle'

Jonathon Childers readily admits that his bottom was a high one.

In rehab, he noted the differences — the guys with years and decades on him, men whose consumption had destroyed their bodies and stymied their lives. At first, he told The Ties That Bind Us recently, those differences stood out.

“I would drink because of anything; if I was happy, if I was sad,” he said. “I didn’t need a good reason to, and that was very educational. I was one of those people who went in thinking I would be able to have a beer every once in a while afterward, and I was quickly told that was not the case.

“Just having that revelation and learning about how I change alcohol chemically once I drink and the way those chemicals react in my brain due to excessive use over the years, that helped me out a lot. I was still dealing with character flaws that lead me to drink back in the day, but now I find other ways to deal with it.”

The beautiful thing about it, however, is that those character defects lessen with time and work. It’s a funny parallel to his musical success: As he’s gotten better, so has his band, and today Blank Range is considered one of the hot young tickets of a Nashville sound outside of the country music mainstream. And thanks to sobriety, he’s not only along for the ride, he’s using his story to craft some of the songs that have garnered Blank Range a certain cachet.

None of it, he said, would have been possible had he not gotten sober.

“I was just getting to a point where it was not only interrupting my life, it was interrupting everyone’s lives around me,” he said. “People were very concerned. They didn’t want to live with me, they didn’t want to employ me, and they didn’t want to be in a band with me.”

A 'good Midwestern upbringing'

Courtesy of Wrenne Evans

Childers grew up in Bryon, a small town in North Central Illinois where his father worked as a nuclear reactor operator. It was a modest Midwestern hamlet, and Childers followed in the footsteps of a legion of young people — he went to school, he joined the Boy Scouts (eventually becoming an Eagle Scout) and enjoyed what he describes as a “good Midwestern upbringing.”

“I started drinking and smoking a little pot in high school, as kids do, and went off to college when I was 18,” he said. “My father passed away suddenly, but I don’t know that I would necessarily attribute that situation to my drinking. I think I just liked drinking, and I continued to drink through college. I ended up moving down to Nashville about a year after I graduated to play music down here, and I just continued that lifestyle.”

After graduating college, Childers found himself playing in a band in Urbana, Ill., with Blank Range drummer Matt Novotny; a regional tour took them through Nashville, where Novotny knew guitarist/singer Grant Gustafson, and their group stayed with Gustafson. The three struck up an immediate friendship, Childers moved to Nashville six months later, and Novotny followed six months after that upon completing college, and Blank Range got off the ground shortly thereafter. That was in 2012, and in a town slopping over with musical talent, the group began to make waves.

The band’s sound draws on a cornucopia of influences, but none of them take precedence — lo-fi garage rock that proliferates Nashville’s indie scene, Midwestern Americana and a few scuzzed-out psychedelic flourishes all simmer to the surface of a fine pot of rock ‘n’ roll stew. As a point of reference, the guys fall somewhere along a line between the raw garage-rock of Lucero and the polished alt-country beauty of Dawes, but the guys are proud that they sound a little like those bands and a whole lot like themselves.

“Being able to look back at this year and having gotten to go on the tours that we’re doing, it feels awesome, man,” he said, referring to jaunts earlier this year with alt-country up-and-comers like Tyler Childers (no relation) and Margo Price. “We’re very grateful, because we’re in a position a lot of people would very much like to be in. It’s been a long journey, but each little step like that has been additive to us, and we’re getting to the point now where we can go on tour and come back and not be broke. When you’re in the thick of it and in the day to day, it’s not always easy to see, but gratitude helps me to take a step back.”

Stopping the descent

“I had lost a job because I got drunk before going to work, and I was drinking all the time,” he said. “I would wake up, and I had a bottle of vodka in my room. My band had been concerned, and actually, our lawyer — who was a good friend of mine — reached out to me and introduced me to MusiCares as an option, about six or eight months before I went to rehab.

“It took me a little bit, though. I got fired from a job, and I quit drinking for a week, but I was counting down the minutes. My roommates, who were very, very good at not being enablers of the situation, told me that if I drank anymore, I had to move out. I drank, and they asked me to move out. I had $200 in my bank account, and I didn’t know where else to go, so it seemed like time.”

MusiCares helped him get into treatment, where he discovered that his problem wasn’t a specific substance but a disease. He got out and started going to meetings — 90 meetings in 90 days, as it’s often suggested — and started meeting others in recovery. And he began to mend relationships, especially with his three bandmates, who continue to be his biggest supporters today, he said.

“I’m very lucky to have landed in a situation where there’s nobody in my life who’s interested in seeing me use again,” he said. “Everybody’s very supportive, and they opened their arms to me and gave me a lot of forgiveness for pain that I caused. I got to go back into a situation that was supportive, and I know not everybody gets to do that. But for me, I threw myself back into the work.

“I can get a little obsessive still, but today I can go to a show, I can play a show, and I can spend hours after it talking to fans and making connections with people and remembering to follow up with people instead of having a pocketful of business cards the next morning and having no idea where they came from.”

The blessings of sobriety

Blank Range is, from left, Jonathon Childers, Matt Novotny, Grant Gustafson and Taylor Zachry. (Photo courtesy of Joey Martinez)

In 2017, Blank Range released “Marooned With the Treasure,” a sprawling rock record that’s a reverb-drenched nod to a cosmic American rock ‘n’ roll sound made with equal aplomb as the band’s contemporaries, bands like Blitzen Trapper and My Morning Jacket. The third track, “Opening Band,” is a Childers original, and it’s a direct connection to his recovery, he said.

“I don’t think I would have written that song without going down that path,” he said. “Going through rehab and being involved in the program made me think a lot about where there is beyond what’s just in front of our faces on this earth. I did a lot of reading, and I was doing a lot of meditation at the time and listening to a lot of New Age music, which I still do.

“I was living in the moment for the first time in a decade, and ‘Marooned With the Treasure,’ I think that record would not have been made if I hadn’t gotten sober. Or at the very least, I wouldn’t have been on it.”

But he was, and he’s also on “In Unison,” the sleeker, more refined new Blank Range album that’s scheduled to drop in February. As busy as 2018 has been, the tour cycle around the new record will be even more demanding, but sobriety helps with time management, among other things, he added with a laugh.

“Every time I would play a show before, I would say, ‘I can probably have five beers before we play and still be fine!’” he said. “I was always counting, and that’s one of the things that I’m most grateful for is removing (alcohol) from the equation removes all that guesswork. I still shake my head over all the time I wasted figuring that stuff out.”

As for the rest of his life and his music, that’s an ongoing process of development and work — but he’s grateful he’s around and clear-headed enough to do such work. He’s living with friends in East Nashville, working at a bar when he’s not on the road and loving life in a way he didn’t realize was possible pre-sobriety. And when those looking for suggestions ask him how he did it, he’s as plain-spoken as possible.

“I am by no means the poster child for being in the program or for sobriety in general, but I like to show people through my actions that there’s joy in a sober lifestyle, and that there are benefits,” he said. “I try to always support people and to let them know that MusiCares is there. More than anything, I try to let them know that things are clearer if you follow what we’ve been up to.”

Check Out These Other Artists' Stories