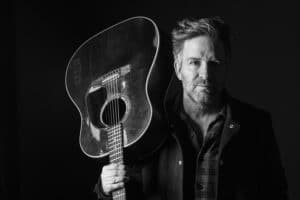

Edwin McCain’s moment of clarity: ‘I had the plan and the gun and the bullet’

Edwin McCain's moment of clarity: 'I had the plan and the gun and the bullet'

In the 21st episode of the classic comedy “WKRP in Cincinnati,” deejay Johnny Fever takes an on-air alcohol test alongside fellow personality Venus Flytrap and a police officer.

Such stunts were classic radio bits in the ’70s and ’80s, aimed at giving listeners an audio demonstration of how quickly alcohol impairment can slow reflexes, slur speech and turn those who take part into inebriated lushes. Johnny Fever, however, went the opposite direction, and that’s exactly what it felt like for singer-songwriter Edwin McCain when he started his dance with booze as a teenager, he tells The Ties That Bind Us.

“I was the guy who got better,” says McCain, who rose to fame as an alternative rock star in the mid-1990s with hits like “I’ll Be” and “I Could Not Ask For More.”

“I was the guy who got better,” says McCain, who rose to fame as an alternative rock star in the mid-1990s with hits like “I’ll Be” and “I Could Not Ask For More.”

“At places like Talbott (Recovery, in Atlanta) and CDAP (Center for Alcohol and Drug Programs, an arm of the Medical University of South Carolina) in Charleston, they’ve actually show that there are some teenagers that drink alcohol who experience no negative consequences,” McCain continues. “It lights them up, and they just do better. They’re the kids who can handle it right out of the gate. Now, that’s almost an 80 percent guarantee for alcoholism later in life, but the fact is that in the beginning, it actually works really well for you.

“For me, I didn’t realize it at the time. I just thought, ‘Dude, I’m good at this!’ I was the kid who talked to the cops when they came to a party, I was the kid who drove everybody home. And I could pop back up and play gigs, because it wasn’t ever a thing. It wasn’t until years later, when we were making a record in the studio, and they had a keg on tap, and at first I said, ‘I can’t drink beer tonight; I’ve gotta cut these songs.’ But then I found myself drinking beer. Or I said, ‘I’m not gonna drink anymore,’ but you end up drinking anyway. That’s when you really do realize that you’ve lost control over it.”

The life of a professional musician, especially one with a modest amount of national success, lends itself easily to rationalization and justification, however. Despite the whispered warnings of the better angels of his nature, it was easy to invoke what McCain jokingly refers to as “the Hemingway clause.”

“You think, ‘There’s all kinds of creative people who were alcoholics, so we might as well just wear it, because there’s no way we can stop it!’” he says. “I remember that being one of those internal dialogues, and because nothing bad was happening, I thought, ‘I can ride this out for a while.’ And I did. It was another decade before I made a space shuttle-sized smoking crater that I had to crawl out of.”

From the top spot to the sweet spot

Like they say in the rooms, however, he didn’t become addicted overnight. He rose up out of the club circuit along the coasts of the Carolinas to form the Edwin McCain Band, which released the album “Solitude,” featuring a guest appearance by Hootie and the Blowfish frontman Darius Rucker on the title track, in 1993. “Honor Among Thieves” followed in 1995, and in 1997, “Misguided Roses” featured the Top 10 hit “I’ll Be.”

Like they say in the rooms, however, he didn’t become addicted overnight. He rose up out of the club circuit along the coasts of the Carolinas to form the Edwin McCain Band, which released the album “Solitude,” featuring a guest appearance by Hootie and the Blowfish frontman Darius Rucker on the title track, in 1993. “Honor Among Thieves” followed in 1995, and in 1997, “Misguided Roses” featured the Top 10 hit “I’ll Be.”

His 1999 record, “The Messenger,” was propelled to gold certification by “I Could Not Ask for More,” included on the soundtrack to the Kevin Costner flick “Message in a Bottle.” After the 2001 record “Far From Over,” McCain parted amicably with Atlantic Records, and he’s continued to release music, but his work has deepened in complexity as he’s gotten older. Some of it has to do with the emotional vulnerability he found in sobriety in 2007; some of it has to do with where he’s at in the seasons of his life. He veers between enthusiasm for the creative process and the jaded outlook of a guy who’s been to the top and discovered that it’s not all that aspiring rockers just starting out imagine it to be.

“I look at the music industry and I’m like, ‘God, we’ve just jumped the shark,’” he says. “The magic of it is sort of gone, because my kids can play drums on their iPads now. Playing instruments is not a thing anymore, and it’s not as amazing a thing as it once was, because they can go on YouTube and watch thousands and thousands and thousands of people play music. When we were coming up, there were only a handful of people we saw in our hometown that were good enough to be impressed by it. The hierarchy just feels way more vast.

“I was a musician of note in Hilton Head, S.C., because there were only like four of them! Now, of 10,000 people on YouTube playing ‘I’ll Be,’ I’m probably in the bottom 8,000 of them as far as quality of musicianship, and I wrote the damn song! It’s an interesting dynamic, and I think I benefited from when I was as much as being who I am.”

Social media, he adds, has taken away some of the luster that rock stars of yesteryear used to have. In the 1970s, the members of Led Zeppelin seemed like gods to their fans because they were removed from the minutiae of everyday life; now, with Instagram and Facebook and Twitter, famous musicians share with fans everything from the brands of underwear they buy to the political allegiances they have.

“I just think, ‘Geez, I’m just not signing up for that,’” he says. “If what I’m wearing matters for the music to land, then I’m not doing it right. I get a lot of questions from people who are like, ‘We don’t understand why you play these 150 seat venues!’ And I’m like, ‘Really? Because when we do that, we share a night of music and everybody gets it and walks out feeling good about what happened, and I don’t have to have an 18 wheeler to carry all of my gear around!’ That’s as good as it gets.

“I’m in the sweet spot right now. Everybody asks when I’m going to make another record, because that’s the polite thing to ask, but they don’t really care. They’re not going to listen if you make it; it’s just something nice for them to say because they know what you do — but they like listening to the old stuff. I joke with the crowds almost every night and say, ‘I have a whole two hours of new stuff,’ and I listen to them groan before I tell them, ‘I’m just joking with you assholes! I’m gonna play what you want!’

“I know what my job is. I’m Don McLean. I’m ‘American Pie’ and ‘Starry Starry Night,’” he adds with a laugh. “I’m gonna be the guy who sings those two songs, and I’m gonna get older and older and you’re gonna come see if I can still sing those two songs until I can’t, and you’re still gonna come, and then you’re gonna walk away and tell people I can’t sing those two songs, and that’ll be the last time.”

He’d pretty much accepted that as his musical future, he continues, until he received a text a few weeks ago that rekindled his enthusiasm. It was from a fellow artist, and almost immediately, he says, he felt his muse stir.

“I’ll make a record with him, and I don’t care if anybody likes it,” he says. “Hell, I might make this record and not release it — that’s the punk streak in me. I blame Black Flag and Henry Rollins. If you tell me what to do, I won’t do it, ever — even if I should, even if you’re right. It’s a horrible character flaw, and I have it in spades.”

'I can't stop this'

That flaw is one of the things that kept him in active addiction until 2007. In fact, McCain credits cocaine for hastening his plummet to the bottom.

“If I was just drinking alcohol, I would have been the 75-year-old guy in rehab who was just coming out of 35 years of hard drinking and realizing that he doesn’t have to live that way, and by that point, it’s too late, because there’s no way of getting any of it back,” he says. “In treatment, I watched that guy a lot, because usually that guy was the guy who only drank alcohol. For me, the introduction of cocaine to the mix hit fast forward, and thank God it did, because I still have part of my life to live and enjoy and understand things.”

Like booze, coke seemed beneficial in the beginning. It worked much like Ritalin does, in that it slowed his ADD and allowed him to focus; when he combined the two, the end result was that he felt normal. Or so it seemed.

“I had a hard and fast rule that I wouldn’t do them before shows, but then I broke them,” he says. “I remember the first time I blew it at a gig, and I thought, ‘Now it’s taken over.’ That should have been the hard stop. I never should have crossed that line, I thought, but I just blew right through it.”

He considered rehab, but like a lot of addicts and alcoholics, the fear of change was still greater than the pain of staying the same, at least for a few more months. By the time he found the willingness to go to Talbott, his thinking had turned suicidal, he says.

“The logic that your mind starts to go through is, ‘I can’t stop this; no matter what I go through, I can’t stop this, and it’s becoming more and more unpredictable,’” he says. “I remember going over to a friend’s house to help him put down some flooring, and he had a half bottle of vodka on the counter, and I don’t even drink vodka — but I drank that, and I passed out on his couch. It wasn’t even a fun thing; it was a, ‘Hey, look at that’ kind of thing.

“And your mind starts saying, ‘This is so out of hand. Somebody’s gonna get hurt — hopefully me, but it’s very possible some innocent person is going to get caught up in whatever consequences are surely coming my way.’ And when you start thinking about ways to stop for good, the suicide solution starts to make sense. You start thinking, ‘Everybody would be better off without me anyway.’ I got to that place. I had the plan and the gun and the bullet, but right at the very last second, I thought, ‘Maybe I should give rehab a try. I can always come back to this.’

“More than anything, what it was, at that point, was that we had adopted our first son, and our second son was just born, and I thought there had to be something more to what they knew about me than, ‘He was a tragic alcoholic,’” McCain adds.

Becoming this guy, not that guy

During his first processing group at rehab, he talked about how close he came; when his peers pointed out that they all, at one point or another, had considered a permanent solution to temporary problems, his eyes were opened. He began to understand his own character defects — the inability to set healthy boundaries, for example, especially in the aftermath of his departure from Atlantic Records.

During his first processing group at rehab, he talked about how close he came; when his peers pointed out that they all, at one point or another, had considered a permanent solution to temporary problems, his eyes were opened. He began to understand his own character defects — the inability to set healthy boundaries, for example, especially in the aftermath of his departure from Atlantic Records.

“I was still loafing along like I am now in the wake of those two hits, but there were a lot of people relying on me to generate a lot of income, and my own personal health wasn’t really being considered, and I wasn’t speaking up for myself at all,” he says. “I did whatever people wanted me to do, because I would rather die than tell somebody no. That all contributed to the unhealthy state of mind where I was medicating this unbalanced life that I had.”

He also began to understand that the rooms of 12 Step recovery could provide a guide back to sanity, if he let them. Before going to treatment, he tried meetings, but like the recovery adage goes, it was difficult to graft new ideas onto a closed mind.

“I freely admit to the jackass I was,” he says. “I sat in there and just hated everybody. I hated the process. And I thought I understood what the manipulation is. I did the dry drunk thing, and I would get online to try and figure out all of the ways the program is full of it.”

At Talbott, he received the spiritual component of recovery, but he also began to learn about the scientific components of addiction as well — evolutionary psychology, the effects on the midbrain and the amygdala. More than anything else, however, he learned that all he had to do was follow the advice of his biggest hit and just “be.”

“When you realize you’ve been carrying these bags of crap around, all you have to do is set them down,” he says. “Going to meetings is a physical acknowledgement of an emotional malady, and it helps you with mindfulness. My sponsor used to tell me the hardest thing in the world to do is nothing.”

With time, he began to see that the program was working in his life. The Promises of the Big Book started to manifest, and today he shepherds his recovery by staying active in service work. The rubber met the road when, three years out of treatment, his wife developed breast cancer, his mother fought a cancer battle and his son was attacked by a dog.

Despite that turmoil, he didn’t have to drink or use. He could, in fact, be the person his family needed, the guy who gives of himself to his loved ones and to total strangers who come to him, bedraggled and needing a bed at a place like Talbott.

“I remember thinking in the middle of that maelstrom, ‘Oh — that’s what this is about!’” he says. “I need to be this guy right now, because if I’d been that guy, all of this would have been a total disaster.’”

Check Out These Other Artists' Stories