Harp maestro Michael Crawley: ‘I committed myself 100 percent’

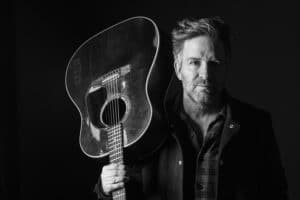

Michael Crawley (right), with his long-time collaborator and guitarist, the late "Detroit" Dave Meers.

Harp maestro Michael Crawley: 'I committed myself 100 percent'

Strolling across the campus of Cornerstone of Recovery, Michael Crawley cuts a unique figure among an already colorful cast of counselors and clinicians who minister to those seeking treatment for addiction and alcoholism.

Whether he’s trotting down to the Caldwell Center to give his standing Big Book lecture or swinging through the Polly Bales Building after a fierce round of circuit training in the Fitness Center that leaves patients half his age in awe of the 63-year-old’s stamina, he’s seldom without a grin, a nickname or some wardrobe accoutrements: earbuds if he’s working out, chains and rings if he’s not.

He’s a bundle of energy, flitting through the dining hall during the crowded lunch rush, hugging clients and colleagues alike. “Yo!” he shouts, slapping the back of a guy fresh out of detox, perhaps one of the men he picks up in a far-flung city and drives to treatment in East Tennessee. “How’s it hanging? You doin’ alright?”

He’s a bundle of energy, flitting through the dining hall during the crowded lunch rush, hugging clients and colleagues alike. “Yo!” he shouts, slapping the back of a guy fresh out of detox, perhaps one of the men he picks up in a far-flung city and drives to treatment in East Tennessee. “How’s it hanging? You doin’ alright?”

Under Crawley’s benevolent smile and magnanimous presence, the man grins, maybe for the first time in a long time; they chat briefly before the harmonica player’s attention is snagged by a co-worker — “Wild Child!” “Doctor Juris Prudence!” The nicknames are affectionate and scattergun, a byproduct of a stage presence honed everywhere from Detroit to Houston to Southern California to East Tennessee, where he’s made his home for the past two decades, earned an integral place in the local blues scene and opened for everyone from Delbert McClinton to B.B. King. He still gets excited every time he recounts the story of his old band, the Detroit Daddies, getting a shout-out by the “King of the Blues” for their performance.

“I was walking back stage when B.B. was out there in front of the crowd, and as I was walking behind the curtain, I heard him say, ‘I’d like to give a special thanks to the Detroit Daddies for opening the show,’” Crawley says. “I couldn’t believe it, man. I was freaking out. I was like, ‘Is this my life? How did it get this good?’”

He knows the answer, of course: Sobriety, which finally kicked in on Dec. 10, 1984, a day that started with a boozy prank that cost him his wife and ended with a slow walk up Meigs Road in Santa Barbara, Calif., with two Heinekens.

“That’s when I decided, if I’m gonna get this, I’ve gotta quit losing jobs, quit breaking up bands, quit breaking up relationships,” Crawley says. “I wasn’t a (jerk), but when I got drunk, I was Jekyll and Hyde. That was my last drunk. I called Dave (Crane, his sponsor at the time) and said, ‘I need to start working on this stuff.’ He just said, ‘Well, let’s go to meetings.’ And this time, I committed myself 100 percent.”

A ramblin’ childhood

These days, Crawley has almost as many years as his father did; the elder Crawley found sobriety in 1964, when Michael — “Crawdaddy,” as he’s known around the East Tennessee music scene — was a young kid. When Frank Crawley did in 1998, he had been sober for 34 years.

These days, Crawley has almost as many years as his father did; the elder Crawley found sobriety in 1964, when Michael — “Crawdaddy,” as he’s known around the East Tennessee music scene — was a young kid. When Frank Crawley did in 1998, he had been sober for 34 years.

“I only saw him drunk once, and it reminded me of me, back in my heyday,” he says. “We were living in Pennsylvania at the time, and I remember he was a silly, sappy, happy drunk. I remember him laughing and carrying on while my mom was crying. That was confusing, but that was the only time we experienced that side of him.”

A paint salesman, his father bought a house in Taylor, Mich. — a suburb of Detroit — with help from the G.I. Bill; nicknamed “Taylortucky,” the community was briefly home to the Crawleys before the family patriarch was transferred with his job. Crawley remembers “a lot of Mayflower boxes” in those years, as the family moved from Taylor to Parma Heights, Ohio; to Parkersburg, W. Va.; to Johnstown, Pa.; to Dearborn Heights, Mich.; and finally back to Taylor, where they would stay. The younger Crawley was in fourth grade at the time, the second oldest of four brothers, and it was another three years before he and his friend, Barney, got drunk for the first time.

“My dad was sober, but he still kept liquor in the house, because he had friends who drank, or my mom would occasionally have a cocktail, or they’d have couples over for bridge and whatnot,” he says. “Barney and I snuck up in the closet with an empty Skippy peanut butter jar and poured a little bit out of each one. We didn’t know what we were doing, so it was a little of this, a little of that; a little white, a little dark, a little whatever. And then we went over to Barney’s house, because his dad was a big drinker, and we filled it up over there, too.

“It was just a big empty peanut butter jar of mixed liquor, and we did what you would normally do when you’re a kid, because you don’t know any better: We drank it straight. He guzzled half, I guzzled half, and we were off to the races. Everything that happens when you get drunk happened in that one night: We laughed, we cried, we tried to chase girls, we got into a fight, we puked.”

The next morning, his father woke him up early to help his Uncle George move. The after effects were horrific, he recalls.

“It was the most excruciating, painful hangover imaginable, and I can still remember it — sitting on the porch exhausted and drained and wondering, ‘What the hell did I do?’” he says. “But that didn’t last long. The pain wears off, and like a lot of us do, I was back to the races.”

He spent his teenage years putting away bottles of Colt 45 and Boone’s Farm wine on the weekends, camping and going to school functions with friends and doing what so many adolescents do: have fun. What he didn’t realize, he points out, was that the road upon which he was traveling would eventually lead him into the wastelands. In high school, he added pot to the mix, buying weed from older boys in order to fit in, and around that time, he began to discover the siren song of rock ‘n’ roll.

His father had begun his musical education, introducing his son to everyone from Nat King Cole to The Ink Spots to show tunes from “South Pacific” and “The Music Man,” and growing up in the late 1960s, he and his brother Brian were avid fans of The Beatles. When he was 8, Crawley received his first harmonica from his grandmother; he taught himself to play “Love Me Do,” and he met a local kid named David Allen. The two swapped records, and Crawley’s palate began to expand; together, the pair formed Ernie and the Neighborhood Gang, Crawley’s first band, and hit up every show that came through the Detroit area.

“I was going to shows and getting fired up about being in a band, and that was when I started taking copious amounts of LSD,” he says. “I also started smoking what I thought was THC but ended up becoming PCP, and I got into a terrible rut with that, man.”

After high school, he continued to play music, but PCP scrambled his brain, and his father eventually committed him to Eloise, a psychiatric hospital in the Detroit area.

“We got Thorazine once a day, and you’d go see a psychiatrist once a week — Dr. Ha,” he says. “I was boofed out of my brain, smoking PCP so bad I could barely tie my shoes at one point, and they’ve got me on Thorazine, talking to Dr. Ha once a week with no other therapy at all — no 12 Steps, nothing. So once I got out, I started smoking pot and drinking beer, thinking that was safe.”

Searching for a purpose

The experience was the catalyst for Crawley’s departure from Detroit. A friend’s father was a union steward for UPS in Houston, so his son and Crawley hit the road in the mid-‘70s and moved to the Lone Star State. Within a few weeks of his arrival, Crawley was working three jobs — part-time for UPS, loading trucks with the Teamsters and pumping gas at a service station, where a customer told him about a company called Global Marine.

The experience was the catalyst for Crawley’s departure from Detroit. A friend’s father was a union steward for UPS in Houston, so his son and Crawley hit the road in the mid-‘70s and moved to the Lone Star State. Within a few weeks of his arrival, Crawley was working three jobs — part-time for UPS, loading trucks with the Teamsters and pumping gas at a service station, where a customer told him about a company called Global Marine.

He’d already driven down to Baytown, Texas, and obtained his Merchant Marine Z-Card, a document that allowed him to work on offshore oil rigs. He was on a waiting list with Exxon, but Global was hiring immediately, the customer told him. He drove back to Baytown on a Tuesday evening, received a job offer that night and was on his way to Louisiana the next day, where he was flown to a Gulf of Mexico rig to work as a cook.

“At that time, I was just a functioning drunk,” he says. “I realized dope kind of smacked me in the back of the head so hard with the PCP thing, which shook me to my core, so I mainly did lots of drinking and smoking (weed). I moved back to Detroit, got a really nice place and a nice car, ran into some musical buddies and started a band called Money Talks. We started playing every night, doing a lot of covers, and that’s when I really started getting serious about the harmonica.”

The guys would call a time out during his rig hitches, and when he returned stateside, he drank “like a madman,” he says, living up to the rock ‘n’ roll stereotype of a hard-partying frontman. He spent a couple of days every month going through alcohol withdrawal just to be able to go back to the rig sober, until one day a friend bet him $100 that he couldn’t stay sober for a month. He tried it, and things immediately got better — he socked more money away, the band started getting more gigs and when it broke up, another one took its place relatively quickly. But on a whim, he cracked open a beer one day, and the whole miserable cycle started again. Not only did he lose the bet, he lost his place to live. He moved back in with his parents and quit the oil rig job, opting instead to pursue music full time.

Within 18 months, he was broke and drinking as hard as he ever had. A friend told him that his old job on the derrick was open, the caveat being that it had been moved to the Pacific, and he’d be based out of Santa Barbara. Crawley didn’t hesitate to accept, not after getting his car stuck in the snow one too many times in Detroit. He drove his Dodge Magnum to the West Coast, moved in with his old rig buddies and started the final leg of his journey to the bottom.

“I was back to being a drunken sailor, buying cocaine, spending all my money on it and working on for three weeks, off for three weeks,” he says. “I met this lady named Diane, and I thought I was in love. We ended up getting married within six months.”

When the company pulled its drill back to the Gulf Coast, Crawley stayed in Santa Barbara. Diane was distancing herself from the drunken revelry of Crawley and his crowd of fellow partiers, and she began expressing concern for his drug and alcohol use. After one particularly excruciating three-day binge, she convinced him to go to a 12 Step meeting in Goleta.

“I was at my wit’s end — shaking, sick, couldn’t keep anything down — and I called my dad and said, ‘I think I’ve got a problem,” he remembers. “He basically said, ‘Do me a favor: Call your central office, find out when the next A.A. meeting is, then call me after you go.’ I waited a couple of days to heal and lick my wounds, and then on a Friday night, I walked into a speaker meeting.

“It literally lit me up. These people were just alive, shaking each other’s hands, drinking coffee, patting each other on the back, yukking it up. I had no clue about 12 Step stuff; I was just there, but then a lady named Nugent got up — and being from Detroit and a fan, I took that as a sign. She was like a female version of me, except she had five years clean and sober. She was saying things that made so much sense. Everything out of her mouth just flowed.”

Testing the waters of sobriety

Michael Crawley (center) with members of his East Tennessee-based blues-rock outfit, Crawlspace.

He didn’t return to the rooms right away, but when he did a week later, he introduced himself. Crane was at that meeting, and afterward he gave Crawley his number. Back home, Diane encouraged Crawley to call Crane and ask for his sponsorship.

“I did, and we became instant friends until the day he died in 2005,” Crawley says. “I met him on Aug. 3, 1984, but it took me another four months to get this.”

Dave gave Crawley service commitments in the program: Make coffee at one meeting; greet people at another. Looking back, it’s easy to see that the stones in the path of his relationship with Diane, combined with a lack of interest in the Steps, contributed to a bad decision to go snooping in his roommate’s desk, where he found enough residue to snort a couple of rails of coke. And so began a four-month run in which he persevered with meeting attendance, always identifying as a newcomer, but never fully getting back into the middle of the boat.

“In California, they always asked the newcomer to stand, so I always stood up every time after I used, and one day, I was at a meeting, and I stood up for like the 13th time in a couple of months, and this guy named Paul comes up to me afterward and goes, ‘When are you going to go any lengths to get this, man?’” Crawley says. “Here’s this nice guy with a really good demeanor, yelling at me: ‘When are you gonna get this? When are you going to go to any lengths, because I’m sick and tired of you standing up!’

“He really had a lot of compassion about me being sober, and I had to admit: He was right. But I still had to go out one more time.”

And so the fateful day of the end of his marriage rolled around. Up all night, having borrowed a neighbor’s stash of booze and having done lines of blow with his roommate, he pulled a stunt that sent her packing. He went to a meeting later that night, still drunk, and stayed silent, slumped in a corner. Afterward, he bought those two Heinekens, climbed that hill and looked out over Santa Barbara and made a decision.

“When I was younger, I went to jail for drunk and disorderly, but I never went to prison, even though I hit parked cars with my car and drove drunk a million times,” he says. “I always thought, there’s a reason why I never did. Spiritually, there was a Higher Power going, ‘I’m going to take you to that line and make a quick left, but it’s going to be an eye-opener.’ All of it just accumulated, and I just got sick and tired of not being happy and of not having something fulfilling in my life. When Diane left, it was a turning point for me.”

Under Crane’s guidance, he started attending meetings, reading the Big Book, working Steps and believing that the program would work — and it did. He began playing music with other guys in recovery and was active in the Santa Barbara scene until the expensive lifestyle and the lack of opportunity, combined with a relationship he was in with a girl from East Tennessee, brought him East. They moved to the Knoxville area in 1992, and it wasn’t long before he found his place in the local music scene.

He joined a group called Bluefish that eventually transformed into Crawdaddy, a band that would soon include two of Crawley's long-time collaborators — the late “Detroit” Dave Meers and the late Rick Wolfe. Crawdaddy enjoyed a long and prosperous career in the local blues scene, winning runner-up for best blues band a couple of years in a row in the annual readers’ poll of Knoxville’s alt-weekly newspaper. The band broke up in the late ’90s, but Crawley reassembled most of the pieces into The MacDaddies, a band that would eventually include Meers and Wolfe. He and Meers eventually revived the Detroit Daddies on a smaller scale, a lean-and-mean stripped down affair with a Sonny Terry/Brownie McGhee feel, and he also fell in with the trop-rock circuit that took him up and down the East Coast.

Flipping the script

These days, his abilities are in demand by a number of projects. That list is almost as long as the one of bands he was once a part of but no longer exist — the Drunk Uncles, Jenna and Her Cool Friends, the Tall Daddies. He’s still part of the Old Time jugband Y’uns, has his own full band Crawlspace and plays in a duo with keys ace/guitarist Stevie Jones called Crawdaddy Jones. On any given weekend, he bounces from gig to gig, supporting local artists and always keeping a harmonica in his pocket because he never knows when he’ll be asked to jump on stage and jam.

He’s got steady gigs for both the public enjoyment and in the corporate world (he’s one of Cornerstone of Recovery’s go-to musicians for entertainment during conferences that the center hosts), and he’s made no secret of his own sobriety. In that respect, he often gets asked for advice by members of the East Tennessee music scene, and he’s always ready to give back what was so freely given to him.

“I tell them, go to a meeting a day until you start wanting to go to meetings,” he says. “Do that, plus make commitments. Fellowship. Greet people. Hand out your number. All of those are things Dave taught me throughout the first six months of my sobriety: Show up early, stick out your hand and introduce yourself. G find yourself a stranger — not just a newcomer, a stranger — and give them a hug. I just tell them to do those things until they really start to like it, and they’ll eventually find themselves getting into service that way. That’s how I did it, and how I fell in love with the program.

“The more you do it, the more responsible you get at your choices in who you’re going to hang out with and what you do. The bottom line is that you have to change. Not all at once, but most everything. Me, I couldn’t have scripted my 30 years of sobriety any better. Recovery is my life now. I don’t wear it on my sleeve, but I wake up every morning, say my Third Step prayer and whatever little prayers I say to start my day and sit and be still for a little bit longer until I wake up and make my coffee, and then I thank God at the end of the day.

“And everything else in between,” he adds with that wise-guy grin, “is like gravy.”

Check Out These Other Artists' Stories