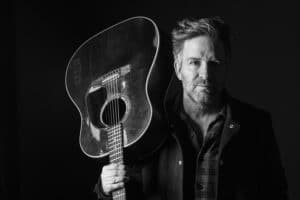

Knoxville’s own Davis Mitchell: ‘I just had to surrender to the process’

Knoxville's own Davis Mitchell: 'I just had to surrender to the process'

For most of his life, musician Davis Mitchell has sought external balms for his internal soul wounds.

“I can recall being obsessed with things like baseball cards, to the point I would shoplift them,” Mitchell tells The Ties That Bind Us. “My whole family used to drink, and I remember my granddad used to sip Miller ponies. I used to sit beside him while he smoked a cigarette and sipped on those things, and he would give me sips when I wasn’t even 5. I remember when I was 5, he gave me a whole one, and I drank it and loved it and was ready for another one.”

In other words, he said, his addiction was active before he ever knew what it was, and certainly long before he knew that the solution was a spiritual one. It’s an inside job, in other words, and one he continues to work through daily maintenance to keep those demons at bay.

After all, he knows all too well just how deep those wounds go, and as far down into them as he’s traveled, he realizes the only bottom is death.

“It’s a pattern for me, and I can see it clearly,” he says. “It’s life or death for me now.”

From Prince covers to Skinny stages

“I had a roommate named Jeff who played the guitar, and he just had an acoustic,” Davis says. “At the time, I was really into Prince’s music, and I said, ‘Man, I just really want to learn some of his songs.’ I loved it, and I wanted to play it and connect with people the way he had. I wanted that, because I don’t think I had ever felt connected to anyone, in any way. And once I got into learning the music and realized what that connection with people would bring, that fueled the obsession. I loved the music part of it, but I craved the connectivity.”

Shortly thereafter, he put together the band Mr. Skinny, which enjoyed a strong regional following in East Tennessee and beyond. The guys described themselves as “funk-oriented groove with an improvisational twist,” and at a time when the East Tennessee music scene was developing a reputation as an incubator of talent every bit as fresh as that in Austin, Texas, or Athens, Ga., Mr. Skinny was a welcome addition.

“In retrospect, I think we were young and had stars in our eyes; it was the time of Phish and Disco Biscuits and all that stuff, and I think we could have become something like that,” he says. “We probably could have done that for years and done fine, but as far as making it on the radio or something like that, I don’t think we were ever close. But we were young, and you could get all the alcohol and cocaine you wanted.”

Mr. Skinny toured as an opening act for everyone from fellow groove-based outfits Gran Torino to the Southern rock/world music ensemble the Derek Trucks Band, and it was while on tour that Mitchell was introduced to the drug that would consume him.

“I remember somebody saying, ‘You’ve never done cocaine before?’ And I said, ‘No, but I’d like to try it,’” he says. “I remember that first hit, and that peace that came over me that I’d been looking for my entire life, and I even told somebody that. I chased that for years, but I never got it again, even though I sure tried to.”

Darkness descends

“I’d see the sun come up four, five days a week, just drinking and doing cocaine,” he said. “I remember calling one of my buddies up one morning after a hard bender and saying, ‘Hey, man, I don’t know what’s going on, but I think I’ve lost control of this thing.’ And he said, ‘We’ll get you some help.’ That was my first introduction to drug and alcohol treatment.”

He went to residential inpatient at a facility in Columbia, Tenn., spending the first couple of weeks sweating and pacing while the drugs left his system. By month’s end, he was in a good place and even picked up a 30-day chip before he coined out. His faulty thinking, he says, led him to lay all of his problems on cocaine.

“I had a girlfriend pick me up, and the first place we stopped was at a convenience store for a beer,” he says. “It wasn’t a week before I was back in (a club), hunting down some cocaine.”

His disease began to mutate as well: He started drinking in the mornings, something he’d never done before, and so he opted for what’s known in recovery as a “geographical cure”: a change of locations based on the premise that one’s problems will be left behind.

“I thought that if I moved, there would be no chance I would meet the kind of people who were causing me all this trouble,” he says. “It wasn’t two weeks after moving to New York City that I found those same kinds of people. I ended up hunting them in bars and looking for the signs; all of the things we look for and recognize in our own kind.”

His downward spiral continued in New York, where the streets were far less accommodating than the ones of his hometown. He remembers sleeping on park benches and in train stations, and by the time he reached out to an old friend — Robby Mathis — back in East Tennessee, he was emotionally, spiritually and financially bankrupt.

“I was ready to die,” he says. “I couldn’t get high anymore, because nothing worked anymore. I was stealing beers from convenience stores and doing anything I could to change the way I felt, or not feel at all.”

A resurrection, and a stumble

Mathis bought him a bus ticket back to East Tennessee, where he lived at the Knox Area Rescue Ministries shelter and took part in the faith-based program there. He graduated that program in November 2002, and by that point, he had begun to resurrect his music career. For several years, Dishwater Blonde added some much-needed R&B firepower to the East Tennessee scene, and the band played major concert series, local clubs and even the Bonnaroo Music and Arts Festival in 2005, when it was chosen as one of a few local acts to represent Knoxville.

Mitchell managed to stay clean for a decade, moving fluidly between two worlds — the faith-centric stages of a club like the old New City Café to the rock venue Blue Cat’s, both within a block of one another in Knoxville’s Old City. In the end, however, his focus on music took away from the work on himself.

“I really think, in retrospect, I put all my energy and time into the hustle of that band, and even though it was a good thing, it was not the thing I needed to focus on,” he says. “I went straight from the mission back to playing bars and clubs really quick without doing the work I needed to do to get a stable base.

“I spent 10 years without putting a substance in my body, but there were character defects that popped up during my marriage and other areas of my life, and those kinds of things bring stress on. I stopped going to meetings and stopped working Steps and stopped calling my sponsor, and finally, after 10 years of fighting it off, I gave into the thing I knew would give me some relief. And you talk about awakening a beast!”

After his relapse, he only stayed in addiction a few days, but it ended with Mitchell in the hospital. He relapsed again in 2015 and 2016, and both times, he wound up hospitalized again, the last time in critical condition in the Intensive Care Unit.

“It didn’t take long for it to take over and wreck me,” he says.

Rebuilding a solid foundation

“Celebrate Recovery has made a huge difference in my life,” he says. “I’m not just going to meetings; I’m working the program. I think I’ve finally found that peace I was looking for in a hit or in a bottle. It didn’t come all at once, and it’s still a work in progress, but I’ve done some of the work this time that I’ve never tried to do before. I’ve got a new sponsor who really pushes me this time to get in and do the work, and it’s made a difference.”

He works in maintenance at Fountain City United Methodist Church in Knoxville — “I’m a janitor!” he says with a laugh, and without a hint of embarrassment. He also leads worship on Tuesdays for Celebrate Recovery and on Sundays for Fountain City UMC, two crucial components of giving back that keeps him on the righteous path, he adds. There’s truly a peace in his voice that’s been missing for a long time — perhaps always — and he recognizes it when he sees the serenity in the eyes of the guy staring back at him from the mirror.

“For me, I just had to surrender to the process,” he says. “It’s been work, but it’s been necessary work to not only stay clean but have some peace. I’ve been clean before, but I had no peace.”

Where the path will lead, he has no idea — but as long as he’s taking the right Steps, he has faith that it’ll be alright. And, he believes, the music that’s been a constant companion will likely play a role in what’s to come.

“I believe God’s got some more music for me,” he says. “I don’t know what it is yet, but I feel like he’s prompting me to say, ‘I’m not done with that yet.’ I don’t know what it looks like, but I know it’s not playing “Brown Eyed Girl” for 50 people! I think there’s a bigger, deeper purpose to communicate through music.

“That connectivity is something I’ve always craved, and it’s something God has put in me for a reason. Throughout my attempts at recovery, and throughout the different bands, I think God has used it along the way, but I think there’s more out there. I’m just grateful I have a chance to figure out what it is.”

Check Out These Other Artists' Stories