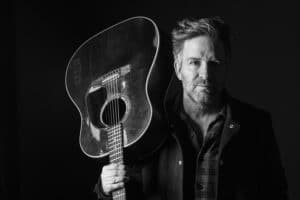

ROCK TO RECOVERY: Founder Wesley Geer pushes back against addiction’s darkness with rock ‘n’ roll

ROCK TO RECOVERY: Founder Wesley Geer pushes back against addiction's darkness with rock 'n' roll

In six years, Rock to Recovery has grown into an organization with 12 full-time employees conducting 450 music therapy sessions a month in roughly 100 treatment programs, mostly around Southern California.

“Looking back to my time in rehab, there was no music,” Geer told The Ties That Bind Us recently. “We were doing yoga and drawing pictures, but I had my acoustic guitar in the treatment center, and I would play these silly grooves — boom-chaka-boom-chaka — and we would get silly and dance around, and that stuck with me.

“With 22 guys in the center, it gets very cliquey, and that would bring us together and tear down those walls and unite us. And so later on I got to thinking, why don’t I bring music into treatment centers? It’s funny because it’s so obvious now. That’s who I’ve always been. I was the mastermind of Hed PE, and I’ve always been somebody who loves to teach music to people.”

Established on Dec. 12, 2012 — 12-12-12, Geer proudly points out — Rock to Recovery has had a profound impact on the Southern California treatment population, and Geer’s team recently expanded its work to Nashville. Geer serves as the program’s administrator, ensuring that despite its growth as an awareness advocacy organization, it remains dedicated to the core principles that inspired him in the beginning.

“The Rock to Recovery sessions are designed for non-musicians to access the healing powers of playing music,” he said. “We form a band with the clients; that’s kind of our shtick. We pick a topic that’s tangent to the type of recovery program we’re dealing with — adolescent behavioral disorders, mental health, addiction, wounded warriors — and we use that for lyrics, then we write a song, perform it and record it in each session.”

Striving for a connection

A child of divorce, his upbringing was a decent one, he said; his relationship with his mother was solid, and while he’s done work on his father’s absence, he can’t point to that as a source of visceral emotional pain that caused long-term harm. Internally, however, something yearned for a connection, he added.

“I didn’t know I could just be nice to people, and they would be your friends for some reason; I thought I had to win them over,” he said. “I would lie about things or whatever, and as a teenager, that caused me to get the reputation of being cocky, which meant that people didn’t like me. I remember they would be annoyed and thinking on a deeper level, ‘Gosh, all I want you to do is like me! Why is this not going so well?’ It wasn’t until I got into recovery and got out of self that I began to understand all of that.”

His family moved a lot, which added to his insecurities, he said; every time he changed schools, he fell in with the outsiders — “the rebels, the screw-ups,” he added — and once he discovered weed, it became a steady source of comfort.

“I took to it like a duck to water; I was stoned all the time, and I got kicked out of high school for smoking weed,” he said. “But I didn’t quit; I just went to move in with my dad. I was smoking weed all day every day, leaving school, and I started playing guitar about the same time. I would go into these weed holes and come out four hours later, and in that sense, I loved it, and it worked for me.”

Adding alcohol to the mix gave him a certain sense of bravado that helped him overcompensate for his smaller stature; his teenage years were spent partying on nights and weekends and seeking validation through relationships, until he eventually started experimenting with cocaine, he said.

“I just though that’s what you did,” he said. “I got kicked out by my dad, and when I turned 18, I was running amok — living in my car, working for Domino’s, until I got a job working at an insurance company with my mom. For a while there, I was doing really well, applying myself and having some success, all the while having these bands that were crappy but were getting a little more real.”

Sex, drugs and rock 'n' roll

“Right around the time I overshot the mark on a Sunday, I got way too drunk and had to go to rehearsal,” he said. “I had come home, and my roommate was snorting something. I didn’t care what it was; I had to snort it too, and suddenly I was no longer drunk. I went to rehearsal and wrote two songs, and that (meth) became my muse for a long time. Artistically, it was doing something for me. I started writing music that was really good for band, and we started selling out clubs and got a record deal.”

The group signed with Jive Records, which released Hed PE’s first three albums — a self-titled debut, 2000’s “Broke” (featuring the band’s highest charting single, “Bartender,” which peaked at No. 23 on Billboard’s Mainstream Rock Tracks chart) and 2003’s “Blackout.” However, disappointing sales left the group in debt to Jive for the advance the label gave the band to cut the first record, and Geer found himself spiraling down a black hole.

“I got off meth, but I turned into a really heavy drinker, and my work ethic suffered,” he said. “Once I got the record deal, I lowered my expectations of myself to meet my using. Did I write as much music or practice as much guitar? No. I would get drunk, chase women and repeat.”

In 2003, Geer left the band as it seemed to be imploding; the relationship with the band’s other co-founder, Jared Gomes, was damaged beyond repair, he said, and his addiction was slowly killing him.

“I had gone from drinking back to drugs, meth and heroin, because I was depressed,” he said. “Something bad would happen, and I would use. That ended me up in rehab, and introduced me to a 12 Step program that taught me all about the disease I suffered from. I bought into the solution and the promises that were told to me would happen. I got the results, and I’ve been a big fan ever since.”

A second chance at rock and recovery

It wasn’t always an easy road. For the first three years, he threw himself into an active and health-conscious lifestyle, earning his scuba diving certification and mentoring children around Southern California. But like a lot of recovering addicts, he slacked off in his recovery, and the insanity returned, he said.

“I knew I couldn’t drink, but then I started believing that I could again, and I went insane again,” he said. “I did that for six months, but I didn’t go back to rehab, because I knew what to do. I went back to the 12 Step rooms.”

For a period, he resigned himself to the idea that he wouldn’t be able to play music again. At shows, he felt a palpable and powerful yearning to still be up on stage, and despite the success he’d enjoyed with Hed PE, he couldn’t figure out a way to let that desire go.

“My brother tried to tell me, ‘Man, you went farther than 90 percent of people; now you just have a normal life,’ and I tried to buy into that, but I wasn’t happy,” he said. “I did a lot of praying and meditating about getting back into music, but there was no way I could start a ‘baby band’ and go back to touring in a van again.

“But within 10 days of praying and meditating, Munky (James Shaffer) from Korn texted and said, ‘You want to come play with us?’”

That was in 2010; for the next four years, he toured and performed with the band around the world, playing in 42 countries at almost 200 live shows. And he stayed sober the entire time, he added.

However, when original Korn guitarist Brian “Head” Welch opted to return to the fold, Geer found himself out of a job.

“I was an out-of-work musician who’s sober, so I went back to the teachings, which say to pray for yourself if others are to be helped,” Geer said. “I had these conversations with God, and it felt like I was preordained to be a musician. I wasn’t destined to be a broke musician who hates his life and is sober; I knew I was supposed to help people and make a living at it. And that’s when the idea of Rock to Recovery came to me.”

Rock to Recovery is born

“What happened was that I would pitch it to people, and they would say, ‘Oh, that sounds great!,’ and then when I would tell them it was my idea and ask them to hire me, they would say, ‘Eh, no,’” he said with a chuckle. “I pitched it to everybody I could get connected with until finally I just thought, ‘This isn’t going anywhere.’ Finally, I went to one of my friends from back in the day, the club days, and he said, ‘I love it.’

“He said, ‘I want to give you a chance to do it, and I’m going to stand behind you in this concept. It might even suck in the beginning, but I’m not going to give up on you, because I believe in it.’ And he gave me that chance.”

In the spring of 2013, he got his first opportunity to put Rock to Recovery into action. With only two weeks to prepare, he was suddenly faced with turning his dream into a reality — and the challenges that entailed.

“My same smart brother pointed out, ‘How are you going to write a song with a bunch of non-musicians? They’re going to fight over the lyrics and everything!’” he said. “I got so scared, I almost didn’t do it, and I kept trying to figure out how it was going to work. But then I saw this TED Talk about ‘Why We Do What We Do,’ and I started thinking.

“Take a company like Apple, for example. They don’t just say, ‘Buy our computer!’ They tell you why you should buy it — because it does this and that and this. And that made me realize that instead of worrying about the outcome — the why — I just had to bring the idea. So I went in and said, ‘I’m here to bring music to you guys, and I don’t know how it’s going to go, but how rad is it that there’s going to be music, and that we’re going to do this together?’ And they said, ‘Yeah, let’s do it!’ The first sessions went pretty well, and that told me this thing would work.”

A man on a mission

Today, Rock to Recovery is spread out across Southern California and is making inroads into other parts of the country. The organization hosts an annual concert every year and presents both Service and Icon awards to musicians who have made a difference — deejay/producer Moby, for example, or this year’s Service Award winner, Tommy Vext of the band Bad Wolves. The nonprofit arm is funded by the for-profit entity, and Geer spends much of his time as the administrator, organizing events and overseeing the behemoth that began as an idea by a rock guitarist who was determined not to let music go.

He still makes time for the work that’s most rewarding — the day before his Ties That Bind Us interview, he spent time at an adolescent treatment program — and he keeps his personal recovery separate from his organization’s mission.

“They aren’t the same, and I learned early on to separate the two,” he said. “I know a guy who was working in the treatment center I was in back in 2004 die, so intellectually, I get it. This is not my program. My program is me, and what I do. I never stop working on what I need to do for myself.”

Rock to Recovery certainly counts as a component of his service work, however. It’s just that Geer has found a way to combine his passion for rock ‘n’ roll, his personal sobriety and his vocation into a mission that helps others find a way out of the darkness with which he’s familiar.

“Being in music, I’m taking the things I love and finding a new way to use it to help people,” he said. “It’s an honor, because there’s always somebody who’s sicker or worse off, and they find that there’s a way to a better life.”

Check Out These Other Artists' Stories