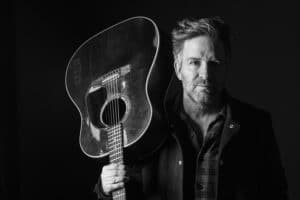

Singer-songwriter John McAndrew: Almost 35 years later, the journey is still beautiful

Singer-songwriter John McAndrew: Almost 35 years later, the journey is still beautiful

It was a lesson long in learning, but singer-songwriter John McAndrew eventually figured out to let the music lead him.

In fact, McAndrew said, every good thing about his music career followed in the wake of his decision to try a new way of life.

“I was several years sober, and I played for an international event in Minneapolis in 2000, and there were 70,000 people at the Minneapolis Metrodome where I sang, and the following Sunday, I met a man named Earnie Larsen, who heard me sing that day, and they were both life-changing events — singing there, and meeting Earnie, who started to mentor me and take me places. Both of those things really changed the trajectory of my career and really changed what I sang about.

“He started taking me to different recovery events, to sing and talk about God’s grace and all that kind of stuff, and those were big, pivotal moments. Soon after, I got my first record and publishing deal with Muscle Shoals Studios in Alabama, and I started coming to Nashville more. I was eventually invited to come and sing at Cumberland Heights, and eventually, because of my work with other treatment centers and with other people in recovery, I was asked to come on board full time four years ago to run the music therapy program.

“It was just a natural fit,” he added. “I believe we’re given uniforms by a Higher Power to do what we’re supposed to do, and this is what I’m supposed to do.”

The allure of the spotlight

McAndrew taught himself to play the piano in the basement of his family’s Minnesota home, and by the time he was 20, he was adept enough at it — along with saxophone, harmonica, guitar and flute — that he earned a spot in a neighborhood band. When the singer’s voice gave out, he asked McAndrew to take over on vocals, and his time in the spotlight lit a fire within him, he said.

“I remember that I got up and sang one of his songs, and I looked up, and one of my older brothers, Emil, was standing there with tears in his eyes,” he said. “I remember thinking, ‘This looks like a good way to get attention.’ That night kind of changed things.”

Shortly thereafter, a snowblower mishap injured his right hand, and the only instrument he could play with one was the piano, which became his primary vehicle from that point forward. Music was in his genes; his father, after World War II, took his clarinet skills (in the Pacific theater, the elder McAndrew played alongside Hugh “Mr. Green Jeans” Brannum and the future music director for TV host Ed Sullivan) and joined jazzman Stan Kenton’s combo, playing up and down the East Coast. McAndrew developed an ear for the jazz that was on the family turntable, and he remembers musician friends of his father always coming over to jam.

“And then my older brother played bass in a country-rock band called North Country that was successful regionally, and those two influenced me a lot,” he said.

As a pianist, singer and budding songwriter, he enjoyed membership in regional country-rock bands for the next several years, working odd jobs during the day and performing at night.

“I didn’t practice very much at anything except drinking, though, and by the time I was 29, it all crumbled down,” McAndrew said.

The terrible beauty of the bottle

“I immediately got really drunk every time I touched it,” he said. “It made me more comfortable to make a fool out of myself, which was the thing to do when you’re Irish and hanging around other people who drink. By the time I was 19, it was daily drinking, especially when I got out of high school and went to college.”

Around the same time, he was hospitalized and diagnosed with Type I Diabetes; concerned with the mild withdrawal symptoms he saw in his patient, McAndrew’s doctor suggested he cut back on his drinking. McAndrew had other ideas.

“I remember at that point thinking, ‘Screw it; I’m gonna die anyways, so I’m gonna go out in a blaze of glory,’” he said. “That last about 10 years, and then I found cocaine … there were needles around, because I was a diabetic … I did all of it.”

His music suffered because of it. Shows would become shambling train wrecks, with McAndrew showing up late, forgetting words to songs or walking off in the middle of a set.

“But what I did, I just lowered my audience down to the level that would accept that kind of stuff, because as alcoholics and addicts, that’s what we do,” he said. “I just went right down to scraping the bottom of places that would hire people like me.”

One fateful night after a gig in South St. Paul, he hit his bottom. He was blacked out for much of the show, but he remembers doing blow at the after-party, chasing it with liquor, and still wanting to die.

“I got in my car, grabbed ahold of the steering wheel, closed my eyes and started driving across this freeway,” he said. “I did that all the way home, screaming and crying and hoping to get hit by something.”

He made it home, and when he walked into the kitchen, his wife made a simple observation: “You’re dying,” she said. “You’ve got to get some help.” McAndrew made an appointment for the following Monday with a facility in St. Paul, Minn., and that’s where his journey began, he said.

“I went in and did the assessment, and I was going to have to wait a couple of months to get into a 21-day partial hospitalization program,” he said. “The guy who did the assessment said, ‘Can you quit drinking by yourself until then?’ And I said, with all honesty and in my Minnesota accent, ‘You betcha!’

“They never stopped me or corrected me; they just said, ‘OK, you come and start treatment on this day, and good luck.’ I stayed sober on my own for a very short period of time, but the last few weeks and months of 1983 were terrible. I got alcohol poisoning, I was suicidal, but that was when I started my new journey.”

The balm of a second chance

His recovery-centric songwriting has led to an exclusive inspirational website, In This Hour; there are plans to add a podcast as well. He was asked to pay musical tribute to guitar god Eric Clapton for the latter’s work with the Crossroads Centre, a substance abuse treatment facility he founded in the Caribbean. He’s recording a new album in Los Angeles.

All along the way, music has continued to open doors put in place by his Higher Power. McAndrew has simply tried to get out of the way and follow that path.

“It’s an incredible journey,” he said. “In the rearview mirror, we start to see God working in our lives, even when we don’t know it. That’s exciting for me. That, and watching a person new to this way of life open up and discover who they’re supposed to be, by using music as a tool to touch those parts of us that are really way deep down in there.”

Check Out These Other Artists' Stories