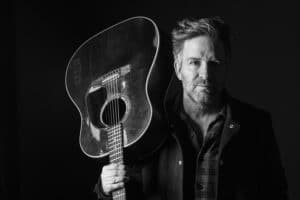

Vibraphone visionary Mike Dillon: ‘My life has gotten 100 percent better’

Vibraphone visionary Mike Dillon: 'My life has gotten 100 percent better'

Mike Dillon, a guy who made his bones playing an instrument that’s often viewed as obsolete in the world of rock ‘n’ roll, is grateful that his brain works differently than those of many of his peers.

“The bottom line is, I play better sober,” he tells The Ties That Bind Us. “I know I do because other musicians tell me: ‘There’s a spark, a glow, in your playing.’”

It’s not that the spark is new — it’s just that after years of dimming it with chemicals, he’s found a way to supercharge it with a clear mind and a clean spirit, and the myriad projects with which he’s involved these days vibrate with the frantic energy of a guy who can’t wait to discover what lies around the next bend. Call it the “eagerness of exploration”: Dillon finds joy and beauty in musical meadows far from the beaten path, and sobriety, he said, has allowed him to frolic there unencumbered by the spiritual drudgery of addiction.

“For me, I figured out a long time ago that there are no rules in music,” he says. “Of course there’s tradition, and ironically, I’d say the more I’ve learned over the years, the more I realize why everything goes back to the one chord and the five chord. If the one chord is home, and the five chord is the grocery store, then all the other chords in between are the stuff you see driving from one place to the other.

“Even in the craziest music, I’ll see right back to, ‘There’s the one and there’s the five.’ I’m not thinking that ‘I’ve gotta have a one chord, and at some point I’ve got to get to the five.’ But there are just some things in harmony that no matter how much you’re exploring, the ear directs what you’re doing.”

The adventure begins

“It was like, ‘That’s cool; I learned this stuff, but now I’ve got to find my own voice,’” he says. “I may not write the greatest music, and I may not be Thelonious Monk or Duke Ellington, but I’m really happy finding my own voice with my instruments and what I do, when I hear a song and go, ‘That sounds like me.’ For me, that’s been my vision quest — to have my own sound, and to make music that doesn’t sound like anyone else. Too many people are being parrots, copying what was done by the greats. I make no judgment of that, but I have no interest in it, either.”

As his classroom education came to a close, however, his drug use began to expand. Like it is for most addicts, the experience was expansive at first.

“As anyone in recovery knows, at the beginning, the drug experience is magical,” he says. “But it’s like a debt collector. It gives you this interest-free loan for a while, but then it kicks in at 59 percent APR.”

Those early days, however, were creative ones: He found his calling on the vibraphone, a percussion instrument comprised of tuned metal bars played with mallets, and it’s one he continues to use throughout his various projects. One of his biggest contemporary joys, he says, is running his vibraphone through pickups and amplifiers, leading a rock band with an instrument that many still consider obsolete. His inspirations include jazz vibraphonists like Lionel Hampton, Terry Gibbs and Bobby Hutcherson, but even jazz proved to be too limiting for the sounds that Dillon wanted to make.

“I listened to all those guys, and ostensibly, you can see that everything has been done — but to my brain, no it hasn’t,” he says. “I hear a million possibilities, and I’m just glad that’s the way my brain thinks. I hear a lot of people out there in the music world doing the same old thing. I’ll go see the latest hot jazz guy, and I always learn something; I’m always blown away, but I leave thinking, ‘That guy sure plays better than me, but I’m way glad I like to explore more than him.’”

And so it was with dope as well: When he discovered heroin, he vowed to remain faithful. Not only did it numb the emotional and spiritual maelstrom inside him, the allure of its creative possibilities was too profound to ignore. Charlie Parker, William S. Burroughs … Dillon saw himself among those ranks, using recreationally and tapping into the drug’s potential to make what he thought would be better music.

“At first it was great; I was in a band, and we got really popular in the Dallas area, as well as in Austin and Houston,” he says. “Back then, I was mainly a weekend warrior, partying after gigs, and I figured out pretty early on that if you snorted a bunch of speed or whatever, your time went out the door and you didn’t play as well. So I would wait until after the gig and do it when we would go hang out, but the problem was the next day.

“I quit going to school around 1987, and it was in the late ’80s that someone turned me on to heroin for the first time. I snorted it a couple of times, and then when I got into Billy Goat (a Latin-funk fusion rock band popular in Texas) and we came back from our first summer tour in 1991, we had gotten a record deal and had money coming in, and that’s when I got a habit.”

Within a year, he went from being the guy who never missed a gig to perpetually being a no-show, and thus began the long downward spiral that eventually led to Billy Goat’s dissolution in 1997.

“There was a guy who worked for our tour manager, and he took me to my first meeting when I was high,” he says. “It didn’t stick, but I remember that was the first place I went where I saw a place where people got their lives together.”

That was in 1992, but it would be another eight years before he could put together 12 months clean, he adds.

“I was in and out; I would maintain for a while, but the thing for me, inevitably when I started a run, was that I would miss a gig, which was the worst thing in the world,” he says. “The band would show up to a sold-out show in Baton Rouge or St. Louis or Chicago, and there were so many times I didn’t make the show. I would clean up for 30 days and promise management I was going back to the rooms. My band was popular, and I thought it was going to last forever. Music, at that point, was enabling my habit.”

New possibilities arise

“People started hiring me; I was getting tours and riding on tour buses,” he says. “I wasn’t borrowing a friend’s van, even though my band made good money, because ours was literally tied together by rope. I wasn’t driving that van eight hours through a blizzard to get to a methadone clinic. Even now, I have a nice van, and I make a van payment every month. It’s amazing to realize that after a few years clean, you can do those things. You can be an adult.

“Last year on tour, our old van dropped the transmission, and in the old days, I’d have to call my dad or borrow money. Instead, I figured out what was happening, walked into a dealership and within an hour, I was approved. Two hours later, I was driving out with a new van. It’s little things like that that you’re unable to do when you’re living in addiction, stuck on stupid.”

Although he hasn’t had a dope habit since 2000, it took a few more years to accept that alcohol, too, is a drug. Ironically, it was other recovering addicts who helped him realize the faultiness of his thinking, he says.

“I’d be at a festival, drinking beer out of a coffee cup, and there would be guys who would come up to me and say, ‘Hey, Mike, I just got my first year!’” he says. “There I’d be at a festival, drinking beer out of a coffee cup with two chicks on my shoulder. And I started thinking, ‘Man, people look up to you, and you’re drinking!”

Now, not only does he not drink, he tries to jog five miles every other day, a habit he credits as “just as important as finding a spiritual solution” to his addiction, he says. Musically, he’s been described any number of ways — “punk rock provocateur,” “jazz vibraphone visionary,” “percussion virtuoso” — and he continues to release music with his own group, the Mike Dillon Band. Last year’s “Life Is Not a Football” is a kaleidoscope of sounds, from Captain Beefheart to Thelonious Monk to the Dead Kennedys, all of it anchored in his desire to make music outside the box of convention, unencumbered by inebriation and unaffected by chemicals that might otherwise taint the purity of his art.

“For me, I had to do a lot of things, and I would tell people who want to change — do 90 meetings in 90 days, and don’t drink or use, no matter what,” he says. “My life has gotten 100 percent better since I quit doing drugs. It’s true what they say — if you write down everything you think you’re gonna get after the first year (clean), at the end of the year, you’re selling yourself short.”

Check Out These Other Artists' Stories